Manufacturers balked at the idea of outlawing an entire technology. Libertarians objected to the idea of government dictating what kind of bulbs people could use in their homes. Even some environmentalists who supported switching to more efficient compact fluorescent light bulbs expressed reservations about requiring consumers to adopt products containing mercury, with no provisions for safe disposal.

But perhaps the most ardent dissenters were those who feared compact fluorescents would turn their home into a place with all the charm and warmth of a gas station restroom.

The uproar was such that the bill never made it to Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger�s desk. Meanwhile, with concern about global warming growing, other states took up the issue (and California eventually adopted new standards), moving legislators on the Senate and House energy committees to take up the lighting issue on the national level last spring.

After more than eight months of intense deliberations between Congress and bulb manufacturers, environmental groups and other parties, a law that requires light bulbs to become more energy efficient became part of the energy bill that President Bush signed into law on Dec. 19.

Over a three-year period beginning in 2012, all new bulbs will have to use 25 percent to 30 percent less energy for the same light output as today�s typical incandescent bulbs. Given that the vast majority of bulbs now on the market that meet those standards are compact fluorescents, which use 70 percent less energy and last 6 to 10 times longer than incandescents, Americans may have little choice but to accept them as part of the future.

For every eager adopter, though, there are plenty of holdouts. �I want to use fluorescents,� said Kath Brandon, a health care recruiter in Denver. �I try to live as green as possible. I telecommute, I recycle, I try to group all my errands together so I don�t have to needlessly burn extra gas.�

But in her experience, compact fluorescents make her house look �dark, cloudy and cavelike.� The bulbs do not emit a �warm, comforting, inviting feeling,� she said. �Your home is your sanctuary,� she said. �It�s where you live and recharge, and it nurtures you.�

The people who design and sell lighting have not been as quick as legislators and environmentalists to embrace compact fluorescents, judging by the dearth of fixtures designed for compact fluorescents in showrooms.

�Designers hate them, and I hate them, too,� said Mitchell Steinberg, the founder of Lee�s Studio, a Manhattan shop that specializes in designer light fixtures. �The beauty of a light bulb is that it gives a warmth. It goes back to fire. I believe people have an innate feeling for fire. We like the setting sun. We like warm color. And these bulbs, although they�re getting better, they�re still not nearly as nice as a regular incandescent bulb.�

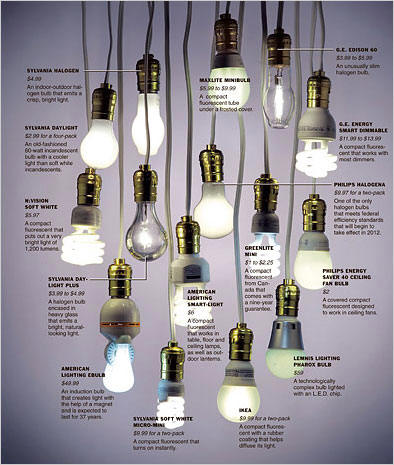

To many people, giving up incandescent lighting means relinquishing some intangible, beloved quality associated with home in favor of a ghastly institutional glow. And the sheer number of choices (not only of compact fluorescent bulbs but of incandescent bulbs that claim to be energy efficient, halogens and alternatives like light-emitting diodes and induction lights), along with the weird shapes of compact fluorescents and the confusing packaging information that generally comes with them, has done little to encourage exploration.

For all the efforts of Wal-Mart to generate sales of compact fluorescents since late 2006, the bulbs still account for less than 20 percent of bulb sales.

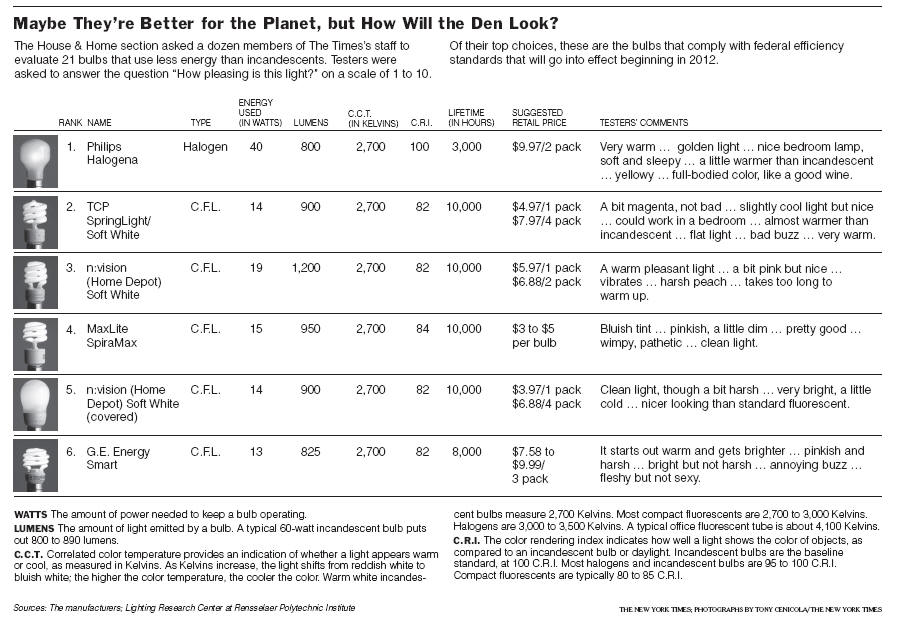

In an attempt to determine whether energy-efficient lighting is as awful as Mr. Steinberg and others believe it to be, or whether some energy-efficient bulbs might cast an appealing light on a bedside table or a living room wall, the House & Home section asked several manufacturers to provide samples of their products. The bulbs had to work in a screw-in base and be appropriate for indoor use, and manufacturers were asked to choose models they believed were closest in light and color to traditional incandescents.

Once the bulbs were collected � 21, including 14 compact fluorescents � a panel of staff members at The Times was asked to judge the quality of the lights. Identical ceramic table lamps with plain white shades were placed at the ends of a long table, one with a traditional 60-watt incandescent bulb for comparison.

THE first compact fluorescent tested, an n:vision Soft White manufactured by TCP for Home Depot, evoked a collective groan. Although some liked its brightness and whiteness and the way its outer shell hid the coil and made it look more like a traditional incandescent bulb, others dismissed it as harsh, comparing it to hospital lighting.

Sylvania�s Bright White Designers Choice was even less popular. Panelists decried the color as sickly and gluelike As other compact fluorescents were tried, the complaints grew louder. G.E.�s Energy Smart Daylight 15-watt bulb looked �icky frigid blue.� Sylvania�s Micro-Mini evoked a rainy day. One tester said the MiniBulb from MaxLite �makes me queasy.�

The judges were fascinated by the way the complexion of the editor who was changing the bulbs shifted, from tan and fit to rosy to pallid to alabaster. After seeing his face under Greenlite�s 13-watt Mini, a writer barked, �Dermabrasion, right away!�

The slight buzzing emitted by many of the compact fluorescents, including G.E. Energy Smart bulbs, Sylvania�s Designers Choice, and TCP�s Spring Light/Soft White, irritated panelists, as did the time it took for some bulbs to light and the flickering that sometimes ensued once they did.

There were a few particularly interesting products, like the futuristic-looking eBulb from American Lighting Industry (951-328-8184), which uses induction technology, an old form of lighting sometimes used in places that are hard to reach, like tunnel ceilings. The $50 bulb uses 80 percent less power than incandescents, its maker said, and is expected to last 50,000 hours, or five times longer than many compact fluorescents, largely because of its round magnet, which helps it recycle electricity. Panelists described its color as �channeling Jules Verne� and said its light looked �O.K. for a tattoo parlor.�

Some judges were enthusiastic about a dimmable compact fluorescent, the G.E. Energy Smart Dimmable, given that such bulbs have, until recently, been hard to find. But rather than moving smoothly from dark to light, as incandescents and halogens do, it functioned more like a bulb with three settings: high, low and off.

Another object of excitement was the Pharox bulb (upscalelighting.com) from Lemnis Lighting, which uses a light-emitting diode, or L.E.D. This technology, which works by illuminating a semiconductor chip, is more efficient than compact fluorescent lighting. But because L.E.D.�s emit directional rather than diffuse light, they are typically implanted in flat surfaces like walls or light panels.

Lemnis is one of a few companies that have managed to apply the technology to a screw-in bulb, but the panel complained about how green its color looked, particularly against the skin. (A photographer, echoing criticisms from others, thought the bulb cast a glow that gave a person nearby an �embalmed look.�)

Not all the bulbs were met with negativity. Panelists favored the light cast by halogen bulbs (including the Daylight Plus and the BT15 from Sylvania, and G.E.�s Edison 60), which last twice as long as incandescents, requiring less energy for the production and distribution of replacements, and are therefore more efficient.

One halogen model, the Philips Halogena, was not only pleasing to the eye � �nice, soft, golden light� one panelist said � but efficient enough to meet the criteria of the new energy bill. Panelists also admired Sylvania�s eLogic incandescent bulb (describing it as �creamy, �cozy for reading� and �nice, even, warm light�), the lone incandescent to be included because it lasts 50 percent longer, measures 30 percent smaller and uses 5 percent less energy than a standard incandescent.

Although most of the compact fluorescents were deemed unacceptable by the panel, there were several that were found to be not only acceptable but attractive. The n:vision TCP Home Soft White, for example, was deemed �a warm pleasant light.� The TCP Spring Light/Soft White was �almost warmer than incandescent,� one person said. And the MaxLite SpiraMax was generally liked, considered �pretty good� and �clean.�

IN the course of testing one of the compact fluorescents, the white fabric lampshade was replaced with an opaque cardboard one. Instantly, the color of the light on the wall, the look of surrounding objects and the sharpness of their shadows were dramatically altered, in ways both pleasant and not.

It was a reminder, as one panelist said, that a bulb�s light may be �no more important than how it�s cast around the room� � or, as another put it, that �you have to look at all the variables: it�s not a one-bulb-fits-all situation.�

Indeed, the right way to think about lighting, according to designers and other lighting professionals, is to go beyond the quest for a bulb that uses the least energy and to make sure you are applying the right technology.

�Lighting doesn�t mean anything if you don�t put the light where you need it,� said Paul W. Eusterbrock, president and owner of the American branch of Holtk�tter, a high-design German lighting company. Warm-toned compact fluorescents may work fine for lighting a whole room, for example, but fluorescent light does not project the same way that halogen light does, so for reading, a single adjustable halogen light could be both the best and the most energy-efficient choice.

Tom Dixon, the British furniture and lighting designer, and an advocate for compact fluorescents, agreed that context is all-important, and that the ways light is cast and fixtures are arranged need to be thought through. Deployed properly, he said, energy-efficient lights can make for a beautiful interior. �What you do in the modern world is mix light qualities anyway,� he said. �You can use C.F.L.�s for overall lighting, and then pick out a couple of objects with halogen spots, and do an L.E.D. wash on the wall.�

He believes the main problem with compact fluorescents is simply a distaste for change. �I�m sure there were the same arguments when gas lighting replaced candles,� he said. �The light�s quality is very different, and it�s going to take people some time to adjust to that.�

The adjustment may not be as hard as some fear. Manufacturers, who are continuing to pursue better light quality for compact fluorescents and light-emitting diodes, are also racing to develop incandescents and halogens that will meet the new national standards. One day soon there may be a much wider range of energy-efficient bulbs to choose from.

Meanwhile, another European designer, Richard Sapper, may be a useful test case for Mr. Dixon�s theory of adaptability. An older man � 75 to Mr. Dixon�s 48 � he describes himself as something of a lighting traditionalist, even if he did pioneer the home halogen lamp with his 1972 Tizio, and design an elegant L.E.D. fixture, the Halley, 33 years later.

He has definite ideas about light in general � for example that �northern light on a day without sun is the only kind that renders color naturally� � and about fluorescent light in particular: �Another problem, besides its color,� he said, �is that it�s always diffuse, whereas incandescent light is coming from a point. And coming from a point it has somehow the quality of sun.�

So it�s perhaps surprising that at his home in Milan, apart from a few halogens on the living room ceiling and several of his own fixtures scattered about the house, all the bulbs have long since been replaced with compact fluorescents. �My wife is very aware of environmental problems,� he explained, and �she doesn�t give me a choice.�

He wasn�t enthusiastic at first. Even now, he said, �I prefer traditional incandescent light. But you get used to it.�